- Sherry Wine:

- Production

- Classification

- Cities & Bodegas

- Tastings

- Analogues

- Authors & Contacts

- Ðóññêèé ñàéò

Sherry analogues

Soviet Sherry Wine (Kheres)

Olga Nikandrova and Denis Shumakov.

The phenomenon of drinks which are called sherry (kheres) in Russia, Ukraine, Moldova and other countries, which formerly comprised the Soviet Union, owes its existence to a number of factors.

First, the work on wines analogous to Spanish sherries was launched in the Russian Empire (in Crimea) in the end of the 19th century, when protection of controlled names of origin was only a concept. So, first wines made in Russia using sherry production method (or some of its elements) were called ‘kheres’ (pronounced almost identically to a Spanish word ‘jerez’), not giving the legality of the use of the name a minute’s thought.

Second, the most active studies on sherries, as well as proliferation and development of sherry analogues in the republics of the USSR, took place in 1930-1970s. At that time, the protection of denominations of origin was more or less well-developed, and what’s more, there was a sherry D.O. in Spain already — but the Soviet Union was traditionally a little bit away from a large part of international agreements. It felt good in the “a-little-bit-away” and produced champagne, cognac, whisky, porto, sherry and even the wine proudly called “Château Yquem”. By the way, since the modern sherry production in ex-USSR countries was launched in Soviet years, we’ll refer to the drinks described in this article as Soviet sherries.

It should be noted that the introduction of sherry-type wines in the Soviet Union was not the result of a conscious effort to reproduce sherry specifically. Sherry was only one of the streams of work. In those days, fortified and sweet wine was much more popular than now — and it was true not only for our country. The USA, Australia, New Zealand and other countries, which are now notable for their dry wine, produced porto-style (more commonly) or sherry-style wine. The production of “sherry-wine” in these countries, as well as in the Soviet Union, was a desire to diversify the range of fortified wines, rather than to challenge Spaniards.

Third, when the USSR broke up, and countries, that formed in its place, began to be torn between the desire to please every side and the aspiration to make money by proven methods in tried and trusted markets, it turned out that the status of drinks with protected names of origin being distributed in the local market and labeled in cyrillics can be a topic of long and sweet talks with reputable European partners. Alongside, the wine, which the local markets were accustomed to, and which was, frankly speaking, morally obsolete, continued to be sold.

All this has lead to the fact that the word kheres (sherry) in ex-USSR is mainly associated with wines from Crimea, rather than with Andalusian wine. And again, the protection of origin applies to the Spanish, French and English names of sherry — Jerez, Xérès, Sherry — and the Russian word “Õåðåñ” [héres] appeared again to be a little bit away from international regulations.

Kheres produced in the Don and Kuban Regions. www.sovietwine.com & www.nostadrink.ru

The situation is, of course, misleading and ambiguous.

On the one hand, Soviet sherry is a distinctive product (with archaic elements), with interesting history and unobtrusive. It is unknown in markets important for Spain and doesn’t compete against Spanish sherry. Spanish sherry, in its turn, practically doesn’t compete against Soviet one in the former USSR markets (at least, due to the price). Thus, everything seems to be OK.

On the other hand, taste and aroma of Soviet sherries are very different from the ones of Spanish sherries (more on this later). And the fact, that in the Russian market Soviet sherry is more widespread (but still being barely noticeable) than Spanish one, distorts the consumer perceptions of sherry in general, which, of course, makes us sad.

Nevertheless.

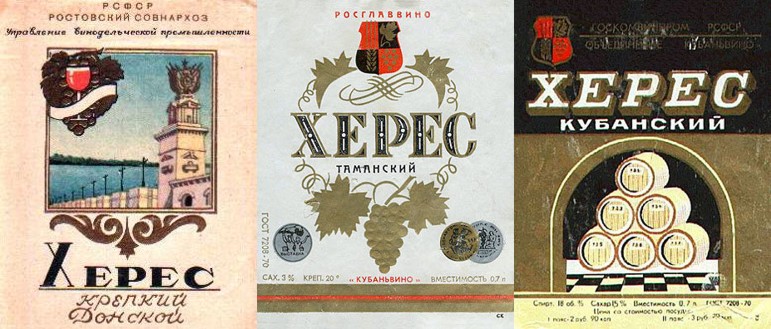

Daghestanian kheres. www.sovietwine.com & www.nostadrink.ru

In the USSR, kheres was defined by the significant consumer properties — as white grape wine with specific “sherry-like” tones in the aroma and taste. The sherry-like tones in wine depend on the presence of aldehydes, acetals, volatile acids and other ingredients; and their amount can be determined rather precisely. Thus, the presence of sherry-like tones in the taste and aroma can be confirmed both organoleptically and laboratorially. It is very convenient.

Sherry-like notes in the taste and aroma are achieved by sherrization of the wine — a processing method of enriching the wine (through the contact with sherry yeasts) with the aforementioned aldehydes, acetals, volatile acids and other ingredients.

Thus, Soviet sherry is defined not so much as a product with particular organoleptic properties, but rather as a product obtained through the use of a particular processing method. Technically, this approach is not much (except for the association with particular territory and grape varieties) different from the Spanish one and, with luck and commitment, can (or could, in the past) produce wine of high quality. Although, the production method of Soviet sherry, of course, is very much different from the method used in the Jerez region.

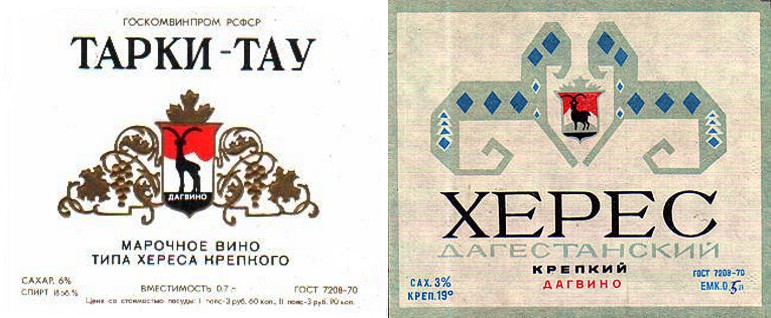

Kheres produced in Uzbekistan, the Kuban Region and Moscow. www.sovietwine.com & www.nostadrink.ru

The basis of this method is sherrization of the wine material. Here classic wine maturing in barrels under a film of yeasts (under flor in the “criaderas and solera” system) is referred to as the periodic film-type sherrization method and is rarely used being considered inefficient. The straightline film-type sherryzation method, when wine interacts with a film of yeasts in special installations which provide for a faster sherrization and (sometimes) automatic control of the process, became more widespread. Only film-type methods of sherrization are used for the production of better Soviet sherries. To produce non-better Soviet sherries some other methods (and equipment) of sherrization are used, such as: interior, film and interior, and filmless.

To enhance the stability of the accelerated methods special yeasts races Kheres 96-K and Kheres 20-C were breeded in the USSR, these races were able to form a film in the wine with 16-17% abv. (in the Jerez Region, the yeasts “work” at 15% abv.). By the way, in Magarach, Crimea, the works on sherry yeasts were started in the early 20th century and were rather successful. Crimean experts clarified the systematization of sherry yeasts and principles of their work, found analogous yeasts in Armenia and other regions of the USSR, and, as was mentioned earlier, breeded yeasts races which were more suitable for our cunning ways of sherry production.

Grape varieties used for the production of the wine material for Soviet sherry are not clearly regulated. It is assumed that every region, which decided to produce sherry-type wine, can find the grapes with required characteristics (sugar content, acidity, etc). For example, in Crimea: Sercial, Albillo, Pedro Ximenez Krimsky, Aligoté, Rkatsiteli, Cocur, Verdello, Sylvaner, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Franc, Fourmint, Gars Levelyu, Traminer, Chardonnay and others. It is interesting to note that at least one of these varieties (Albillo) was used for sherry making in the Jerez Region in pre-phylloxera times.

In most cases, the production of Soviet sherries uses rectified alcohol to fortify wine. This, of course, is smarter in producibility terms than the use of grape distillate, but, in our view, negatively affects the taste of the wine (especially when it comes to ordinary sherries — taste traces of rectificate are less perceptible in wine that was aged for a long time).

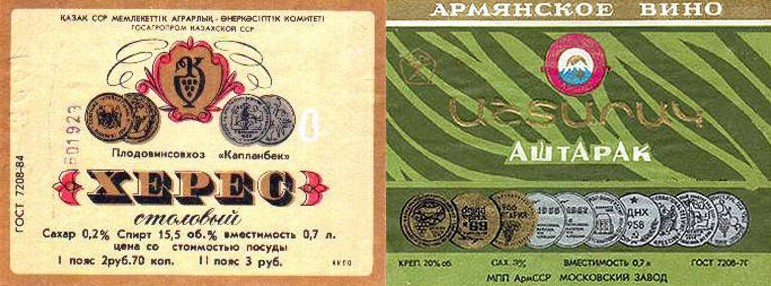

Kheres made in Kazakhstan and Armenia. www.sovietwine.com & www.nostadrink.ru

As a rule, the production cycle of Soviet sherries is shorter than that one for Spanish sherry. For example, the label of “Massandra” sherry (the best one of more for less available Soviet sherries) informs us that this wine has been matured in “oak containers or no less than four years” — and this is considered to be a lot. It should also be noted that Soviet vintage sherries first go through sherrization process under a film of yeasts in the installation for the straightline film-type sherryzation (during one year, for example), and then it is aged in oak containers without any contact with yeasts — in other words, it is then aged oxidatively. With some reserve, by the ageing type “Massandra” sherry can be described as kin to Amontillado.

Now we’re getting to the most interesting and the most useless question connected with the Soviet sherry. This question is: “How is it compared to the Spanish sherry?” The question is useless because most Soviet sherries cannot be compared to the Spanish ones for purely technical reasons. They are produced from different grape varieties. Terroirs are different. Processing techniques are different. The duration of the processing is different. There are similarities only in alcoholic strength and sugar content, but it is still not so simple. It is useless to group drinks according to their alcoholic strength, if you then intend to compare their taste and aroma. So it’s only the sugar content that’s left.

Most Soviet sherries contain about 2-3% sugar — which is about 20-30 grams per liter. In the traditional sherry range, only Dry (and, rarely, Medium), which is made by way of sweetening dry sherry, has the same sugar content. This means, that more or less adequately Soviet sherry can be compared only with Dry. Which is rare and even more rarely happens to be somewhat interesting. Comparing Dry with the best examples of Soviet sherry is meaningless — they are obviously richer. Comparing Dry with the worst examples of Soviet sherry is simply depressing. Dessert Soviet sherries rarely contain more than 100 grams sugar per liter — so they are on the same level as Medium and Cream sherries, but it’s again uninteresting to compare anything with them, since, as well as Dry, they are a bit on the sidelines of the main sherry line.

So, we won’t compare anything. Instead, we’ll enumerate the main regions of Soviet sherry production.

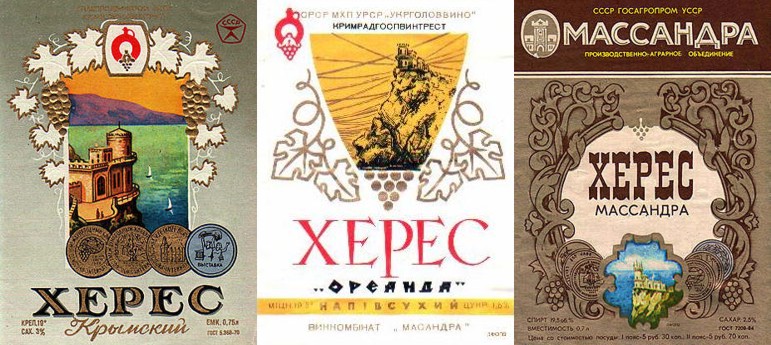

Kheres made in Crimea. www.sovietwine.com & www.nostadrink.ru

The first is Crimea. There are (or used to be) such wine houses as “Massandra”, “Dionis” and “Magarach” — which produce sherries which were (and still are) considered the best ones in the former USSR territory. Besides, these wineries own rich wine collections. For example, Massandra’s collection, which was started in the earliest years of the 20th century and survived the unprecedented evacuation of 1941, includes not only rare wines of the wine house itself, but also unique examples of French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish wine of the 18th-20th centuries. One of the gems of Massandra’s collection is a 1775 vintage Spanish sherry.

It should be noted that none of the mentioned Crimean wineries specializes purely in sherry. On the contrary, sherry occupies a rather modest place in their product range — such a situation was a common practice in the Soviet wine industry. Although, of course, there were exceptions.

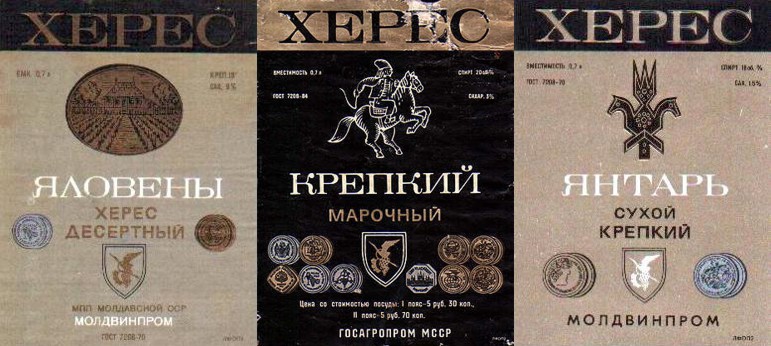

Moldavian kheres. www.sovietwine.com & www.nostadrink.ru

In Moldova, in Ialoveni city, in 1953, a wine house, specializing in sherry specifically, was established. In the past, specialists of this wine house actively worked on the creation of sherrization installations, but they also used classic methods of sherry making. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the wine house was reorganized into a joint-stock company Vinuri Ialoveni. Since 2006, sherriesque wine produced there wasn’t labeled as sherry anymore, it was called Shervin instead. As far as we know, not so long ago, Vinuri Ialoveni company had some difficulties, and it’s not very clear whether it is fully operating at the moment. But Ialoveni wines are still present on the market. On the net, there’s a video-channel and blog by Evgeny Shalar, the director of Vinuri Ialoveni. Here, for example, he’s speaking about sherry processing techniques used in his wine house (in Russian).

Besides the Crimea and Moldova — obvious sherry leaders in the former USSR territory — Soviet sherry was produced in Armenia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, the Rostov Region, Dagestan, and the Krasnodar Region. Most of these wines aren’t produced any longer, but it is still possible to come across the Dagestani (“Derbent”), Armenian and Rostov (“Donskoy Krepky”) sherries.

We’d like to complete our review of Soviet sherries with a couple of remarks. First, top-quality vintage Soviet sherries are called ‘marochny’. The fact that they are attributed to a certain year increases their collector value. Second, there’s quite a lot of information on the Soviet sherry manufacturing process on the net. If you’re interested in this subject, you can start studying it from here, for example (in Russian).

As illustrations for this article, we used labels of drinks which are no longer produced.

Below are ex-USSR sherries which we have tried so far (in Russian):— Shervin (Heres) Armonios De Calitate Matur. Rezerva 1994

— Shervin Ialoveni Romànita 1988

— Îðåàíäà õåðåñ ñóõîé

— Õåðåñ Ìàññàíäðà 1972

— Õåðåñ Ìàññàíäðà 2007

— Õåðåñ ßëîâåíü Ñóõîé 1994

Warning!

This site can contain information about drinks excessive consumption of which may cause harm to health and is unadvisable for people who didn’t come of age.

Share Sherry

- Sherry.wine, FEDEJEREZ

- Copa Jerez, Sherry Week

- Sherry Notes, Jerez de Cine

- Los Generosos, Criadera

- Jerez-Xeres-Sherry

- Los Vinos de Jerez

Articles

- There are more articles in Russian than in English in this website. Sorry :(

Reviews

- To our great regret, we didn’t have time to translate tasting and traveling notes into English. But, if you want, you can see them in Russian.